* This text was originally written for the exhibition catalogue “Portrait Session” at Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

1. About the Participating Works

2. History of the Portrait and the Works by Pamela Rosenkranz

3. Rosenkranz’s Understanding of “Kafka”

4. Understanding the Aspirin; “Thinking about an Effect of Thinking Itself”

5. Wish for Centricity—An Act of Art-Making and the Dismantling of Identity

1. About the Participating Works

In this exhibition, under the rubric of “Portrait,” lots of interesting artists with different backgrounds have submitted remarkable works executed in different media. I put up some of these works, and want to examine them.

At first, the portrait by Hideaki Kawashima—who uses big eyes with completely white hair and skin as his expression—got my attention. Kawashima experienced the ascetic practices of the Tendai sect of Buddhism at the Mt. Hiei-zan Enryaku-ji Temple for two years, from 1995 to 1997. Having read Yukio Mishima and having created art works related to that subject during his school days, Kawashima had made serious works. However, he then changed his style of expression, and started to make portraits of unrecognizable floating-feeling figures, works in which even the distinction between man and woman is blurred. The portrait drawn by Kawashima does not even remain an original color, and in the big eyes, only the emotion is extracted and expressed.

The work “Untitled (Lost Mt. MIWA)” by Ryuta Otake also has a strong presence. Its mysterious white blank space spreads through the big crack in the earth and sends out a mysterious charm, tempting the viewer. The white upheaval appears in the crack in the earth, whose existence was accepted by the exhibiting of the other realistic portrait work, which seems to me a portrait of “woman.” Like the smile on Mona Lisa’s face, the upheaval located in the middle of a crack in the earth is an extremely complex metaphor.

Furthermore, the triptych of works “Cutting a Pots’ Neck” by Kazuna Taguchi deserves special mention. Needless to say, there is a neck on the top of the pot, through which flowers are inserted. However in the second scene of this portrait, the smiling face of Miwa Suzuki, the model of this portrait exhibition, disappears from the neck unnaturally.

First of all, the pot is a symbol of acceptance. It retains water and so makes flowers live; this is the essence of its very function. Taguchi intensifies the loss of the person’s neck by locating this portrait on a pot, the symbol of acceptance. In addition, the pot, which is filled with flowers, is located behind a portrait of Miwa Suzuki, suggesting that the pot that does not contain flowers does not function as a pot. It reminds me of a folk song by Sachiko Kanenobu: “The only thing you did to me is pour water onto the flower, which you broke off.” Of course, in this song, the flower is a woman, and the subject who pours the water and breaks the flower off is a man.

Furthermore, in this work, Kazuna Taguchi goes through a triple process; he has produced the painting, which resembles an existing pot, and he has photographed this painting as well. In other words, this is neither painting nor pot, but rather the photograph which contains an image of the painting depicting the pot. Because a shadow of a photographer (perhaps Taguchi herself) has been cast in this work, we can recognize that this is a photograph. In other words, this portrait is formed on the borderline of three different media—photography, ceramics, and painting.

2. History of the Portrait and the Works of Pamela Rosenkranz

There is one particularly interesting and difficult work: “Portrait of Something I don’t know about You” by Pamela Rosenkranz.

The stick, on a general human eye-level height and painted in a color of human skin, is standing on the egg-shaped mirror, installed on a floor, and is leaning against a wall. When you look into the mirror to perceive the work, you will see your own face and the stick, which together compose a mysterious triangle between the floor and the wall. What does this work mean?

To understand this difficult work, I want to analyze the history of portraiture in Europe, as well as examine Rosenkranz’s work “Aspirin” in the Sato Collection in Hiroshima and her collaborative work with Pavel Büchler “Head over Heels and Away. The Complete Writings of Franz Kafka from Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari” in Bern, Switzerland.

First of all, the emergence of the portrait is related to the recognition of self. “Jiga (means self in Japanese),” in German “das Ich”, involves a recognition process. When we ask a German-speaking artist for “portrait”-themed art work, it may be said that the request inevitably entails creating an art work about self-consciousness. In addition, regarding the emergence of self, recognition itself seems to have been different in Japan and Europe. While I was traveling through Europe, I saw the self-portraits of Rembrandt in the Netherlands, and I strongly felt a European sense of self that does not exist in Japan. Why, then, did I feel such a strong impact from the self-portrait of Rembrandt?

Image 1: “Self Portrait as Zeuxis” c. 1662 82.5 x 65 cm. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Collogne

When we talk about Rembrandt, we cannot avoid talking about two of his contemporaries (roughly speaking) in Holland : Vermeer and Spinoza. Vermeer was born in Amsterdam in 1632, and in the same year, Spinoza was born. The parents of Spinoza had fled to the Netherlands from the Iberian Peninsula to keep practicing their faith of Judaism. When Granada fell in 1492 and Spain completed its Reconquista and became a wholly Christian society, the Sephardim (Diasporic Jews who settled in Portugal and Spain ) were forced to convert to Catholicism or emigrate. Many emigres went to the Netherlands , and this flow of Jewish people brought a new culture into Holland . Spinoza inherited the blood and the history of the Marranos (a Jew forced to convert, which includes those who continued to practice Judaism in secret).Vermeer became a painter who inherited a trend of Rembrandt, who, as it happens, lived in the same neighborhood as Spinoza.

Spinoza took time to study Descartes’s writings and learned the skill of geometric demonstration. Descartes defined substance as “the thing which did not need some others for the existence”; but Spinoza departed from Descartes’s idea of substance. In addition, Rembrandt created many portraits of the Jews who were his new neighbors, and these new strangers became a new group of “others,” necessary to the building of a new identity for the Dutch, who fought to become independent from Spain and embraced a new religious sect, Calvinism, that had emerged out of the Protestant Reformation.

Image 2: “Menasseh Ben Israel ” by Rembrandt, 1636, from Wikipedia

Rembrandt painted a portrait of Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel, who helped found a way of giving the Jewish people the right of residence in England. He was also a teacher of Spinoza. The rabbis of Amsterdam excommunicated Spinoza during this rabbi’s stay in London to negotiate the permission of residency in London, but this excommunication could have been avoided if Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel were part of the deliberations.

At the end of nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, an analysis of Rembrandt was done by Georg Simmel, who sought to find an ideal life of Jewish “foreignness” in Germany. In the book “Rembrandt,” he mentioned that by painting Jewish motifs, Rembrandt internalized the philosophy of Goethe and Kant avant la lettre, and pushed “German style into the highest stage.” Therefore Simmel determined that the Jewish people in Germany living as a “stranger” are not remote people but those who internalized Goethe and Kant; and the Jewish people in Germany, by internalizing German and European personalities but living as Jewish, they “unite both near and far” as a “stranger.” They do not live in their original land, but nonetheless live in the land of their exile as human beings.[1]

I was shocked by the difficulty in understanding Rembrandt’s “portrait,” which I saw on my trip to Europe; but by studying the history, I could finally explain to a certain point that the emergence of this motif shows a difference in the process of self-recognition between Japan and Europe, and is the result of a difference in historical contexts.

3. Rosenkranz’s Understanding of “Kafka”

In the work “Head over Heels and Away”, which Pamela Rosenkranz produced in collaboration with Pavel Büchler as a commission for Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland, they extracted the entire original German text of Kafka quoted in the book Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. The text was presented on the windows of a city centre café, legible to the guests inside but reversed as in a mirror for the passers by. It was also printed as a leaflet, which looks as if the pages just fell out of the original book.

Image 3: Pavel Büchler & Pamela Rosenkranz

“Head over Heels and Away. The Complete Writings of Franz Kafka from Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari”

Deleuze and Guattari first defined minor literature: “Minor literature is not a literature in a minor language, but the literature created by minorities who use majority language.” [2] The language that Kafka used was Czech German as spoken and written by a German Jew living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is not normal German. To quote words of Theodor Herzl—also quoted by Deleuze and Guattari, and also a Jew living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire—who became one of the first Zionists: “In Prague, they were criticized that they (Jewish) are not Czechs, and in Saaz and Eger, they were criticized that they are not German. There were some who wanted to be Germany-like, but then, Czechs attacked them. – And also Germans did.” [3]

In addition, the word “minor” has a very restrictive meaning, and its special meaning can be recognized especially with regard to the Oedipus complex. I will talk about this later.

4. Understanding the Aspirin: “Thinking about an Effect of Thinking Itself”

Next, let’s look at Rosenkranz’s work “Aspirin”, which is in the Sato collection in Hiroshima.

Image 4: Pamela Rosenkranz “Aspirin” close up and installation view

This work is an image of the world-famous headache reliever, aspirin, a white tablet. The image was created by photogram by putting this pill in the center of photo paper. Aspirin has a symmetric conical shape so as to be easily ingestible, and by using the technique of photogram, the light that slid into the bottom of white tablet’s conical shape creates a ring of light as shadow, giving us a sense of a three-dimensional tablet.

When these seven works of “aspirin” are installed on same level, the line of white dots on black backgrounds does not make a straight line. In fact, all tablets are placed at the position where the artist put them, almost though not quite the center of the photo paper. When these seven works were arranged in one line—in other words, when these images are compared to other images—it becomes clear that the white point that seemed to be located at the center point is not exactly at the center point.

Rosenkranz says, “Generally, Aspirin is a headache reliever. To think about its impact is interesting, because it means to think about your head first, and then, the impact of thinking itself.” However, what on earth does it mean to “think about . . . the impact of thinking itself”?

To “think about . . . the impact of thinking itself” is a criticism on the cogito itself. Modern philosophy was formed by the invention of cogito as a concept by Descartes, and cogito brought thinking itself to consciousness. In addition, it was the expectation to give birth to a new divine geometry based on and extending Augustine’s Trinity in Christianity, which needed to be saved. However, it is impossible to “think about an effect of thinking itself” in completely the same subject. A person who logically explained this impossibility is, for example, Kurt Gödel, who wrote the incompleteness theorem, and also Deleuze and Guattari, as I will mention later, criticized this problem by psychoanalytical and timeframe approaches.

Emmanuel Levinas, the person who created the philosophy of others, mentioned that the self is tied to others before its origin. Levinas also mentions that a body and a place that the body occupies is a surplus that I have for subjectivity of transcendentalism.[4] Rosenkranz placed aspirins on an approximately central point, and repeated the same thing and placed these on the same line. This uncovers the gap of centricity, and it exposes the problem of the surplus of the body. Then this surplus creates I as “I.”

Rosenkranz placed these tablets on what she thought to be a “center” and exposed them to light. This white ring, surrounded by different particles of light, is almost like a vanishing point. This ring has a beauty reminiscent of Vermeer’s technique called pointillé, a painting technique of using round points to make highlights, by using the technique of camera obscura, which is an origin of photogram.

However, what is this desire, this wish for centricity? Rosenkranz describes a tablet as “the thing that powder gathered into one.” Even if she was able to criticize cogito, Rosenkranz’s wish for centricity is not satisfied.

5. Wish for Centricity—An Act of Art-Making and the Dismantling of Identity

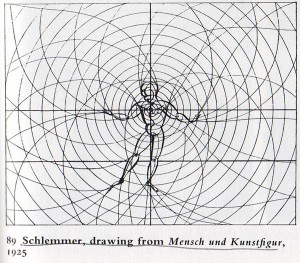

Image 5: Oscar Schelemmer, Drawing from Mensch und Kunstfigur, published in RoseLee Goldberg’s “Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present” P105

As an artist who treated horizontal and perpendicular planes expressively in a cool or even inhumane way, an artist of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, such as August Sander, can be cited here. His centricity is especially German, it may be said. Similarly, one recalls the space recognition of Oskar Schlemmer, a member of the German Bauhaus.

In the drawings of Schlemmer, starting from the body, space expands radially. Descartes invented Cartesian Coordinate System as an extension of his sense of the cogito, but after all, the body of the self is located at the center. Also Schlemmer understood space from the vantage of self, and this idea itself is particularly European, or in other words, particularly related to cogito.

So, let’s return to Rosenkranz’s work “Portrait of Something I don’t know about You” created for this exhibition.

Image 6: Pamela Rosenkranz ”Portrait of Something I Don’t Know about You”

First of all, the mirror placed on the floor invites the viewer to look at a reflection of himself or herself. However, the image that the viewer will see is, of course, the face of himself and herself, and also the triangular shape of the stick, mirror, and the wall. The structure of inviting the viewer to regard the work is similar to that of Marcel Duchamp’s last work “’Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas.” Moreover, the image of a mirror, which invites a viewer, is similar to Taguchi’s pot as a symbol of acceptance. Furthermore, it was Mondrian who recognized the horizontal and the vertical as figurings of woman and man, and here the horizontal mirror and vertical stick can be recognized as evoking libidinal forces.

Painted to resemble a skin color, the stick which is almost of human height is standing on a mirror that is placed on the floor perpendicularly. This stick keeps its own balance from the entropy of frictions that occurs: the weight of stick by gravity, the mirror that supports the stick, and the support of the wall. Of course, without the wall, this balance cannot happen, and the continuity of support creates the angle of the stick. Both this stick and aspirin’s tablet deal with the problem of gravity.

Also the mirror placed on the floor is egg-shaped. The oval, which is an egg-shaped base, is the circle which has two center points. In Europe, there is a custom to place a portrait of a dead person into an oval-shaped frame, and perhaps this custom comes from the recognition of the dead person, the unreachable existence, as another central point unconsciously, thus solving the problem of the existence of the dead person in a real world.

In addition, eggs of amphibians are round, but amphibians keep eggs underwater. However, birds keep eggs away from steep slopes or on the tree to keep the eggs away from enemies to protect them. When a parent bird holds an egg and warms it, if the egg is a circular shape, it just keeps rolling when something wrong happens. However, in the case of an egg-shape, even if it rolls, it turns by making its way circularly, and comes back to an original position. In fact, the eggs of birds which have eggs in steep areas have a more pronounced egg-shape.

Here, the problem is again body and gravity. First of all, gravity is a distortion of time and space. However, a body that exists as a surplus against subjectivity of transcendentalism reacts. Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time was written under the influence of Einstein, but the people who used timeframe to explore self-recognition and criticized subjectivity was Deleuze and Guattari, who wrote “Kafka”.

In addition, a stick leaned against this wall results in a triangle between the wall and the mirrors, and to begin with, the triangle is symbolically related to the awareness of father and mother that establishes self-recognition. Deleuze and Guattari write that the triangular relationship of family (father–mother–child) defines the subjectivity of a child. In addition, in an analysis of Kafka’s “Dearest Father,” which Rosenkranz referred to, Deleuze points out: “One of the related items which creates triangle of family can be rearranged by an item which can make the whole as non-family.”[5]

By not denying the existence of the Oedipus Complex itself, but opening the triangular element that constituted a family to the outside, it was linked to social groups in the case of Kafka, and tied to the American technocracy machine, governmental bureaucracy machine of the Soviet Union, or a fascism machine.

In addition, this triangle seems to accuse the Trinity of logical contradiction with regard to the relationship between father and child in Christianity. “The person who gives word” = father; “word” = child; “love which is transferred by love” = spirit—these were arranged by Augustine as “Father as god,” “Jesus Christ as a child and logos,” and “spirits which were given to apostles,” and god is defined as three different phases and statuses, but the substance is the same.

In other words, the father in a triangle of the family is equivalent to God in the Trinity, and therefore, Deleuze and Guattari will accuse divine power itself as Oedipus, but not as American technocracy machine, governmental bureaucracy machine of the Soviet Union, or a fascism machine.

One question is not about freedom, but exodus. Not about the Oedipus problem concerned with how to become free from the father, but about how to find a way at the place that the father did not find. In other words, the problem is not to recover the domain of self in a family, but to put Oedipus in the world as a non-domain.

Before modern times, there was no concept of human being as a general idea of the individual or separate entity. Naturally there was no universal concept of the human, either. Then, naturally, a problem of subjectivity had been raised. Perhaps the act of art-making is the way that is related to the dismantling of identity. The act of art-making, in other words, is to find a way at the place that father did not find, Pamela Rosenkranz achieved this dismantling of identity in this work, ”Portrait of Something I Don’t Know about You”.

Narcissus was tempted by an image of himself reflected on a surface of water, which is fragile medium. He kissed his own image and destroyed it. So, how about you, as a person who views of this art work? I hope that viewers have a better understanding of Pamela Rosenkranz’s work ”Portrait of Something I Don’t Know about You” , and I set down my pen.

Shinya Watanabe

* Shinya Watanabe is a curator based in New York, and has traveled to 33 countries. He acquired a Masters of Art at New York University.

Reference Book

INOUE, Jun’ichi “Georg Simmel’s Jewish Consciousness” Ritsumeikan International Research, Book 12 No.2 December 1999

[1] INOUE, Jun’ichi “Georg Simmel’s Jewish Consciousness” Ritsumeikan International Research, Book 12 No.2 December 1999

[2] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari “Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature” p27

[3] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari “Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature” p27 Original Text from Theodore Harzl, cite by Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, Annees de jeunesse, tr. Fr. Mercure, p. 69.

[4] Sumihiko Kumano “Introducing Levinas” p 73 Chikuma Bunko

[5] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari “Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature” p17