B. Changing Perception

a. The Bosnian Governmentfs Employment of Ruder Finn

Inc – Shifting a Civil War to an Independence War

In May 1992,

Bosnian Foreign Minister Haris Silajdzic visited the

The following is

an extract from an October 1993 interview conducted by Jacques Merlino, Deputy

Director of the French network TV2, with James Harff, the Director of Ruder

Finn's Global Public Affairs section.

James Harff is the person who popularized the word gethnic cleansingh

and gconcentration camp.h Because

of his job in

MERLINO: What achievement were you most proud of?

HARFF: To have

managed to move the Jewish opinion to our side. This was extremely delicate, as the

dossier involved a major danger. President Tudjman was too imprudent in his

book, "Wastelands: Historical Truth." A reading of his text could find him

guilty of anti-Semitism. In

MERLINO: But when you did all this, between 2 and 5 of August 1992, you had no proof that what you said was true. You only had the two articles in Newsday.

HARFF: Our work is not to verify information. We are not equipped for that. Our work

is to accelerate the circulation of information favorable to us, to aim them at

carefully chosen targets. We did

not claim that there were death camps in

MERLINO: Are you aware that you took on a grave responsibility?

HARFF: We are professionals. We had a job to do and we did it. We are not paid to moralize. And when the time comes to start a debate on all of this, we have a clear conscience. For, if you wish to prove that Serbs are in fact poor victims, go ahead, but you will be quite alone."[2]

b. Fake Report from the

Concentration Camp

This is just one

example of media control inside the

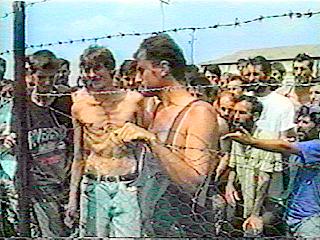

The photo taken by an ITN crew (Tricks of Media)

In August 1992, an award-winning British television team, led by Penny Marshall (ITN) and the reporter Ed Vulliamy from Londonfs Guardian newspaper visited Bosnia but had been unable to find a "concentration camp" at Omarska. Their last stop on the journey was to be the refugee camp at Trnopolje, and it was their last chance to find the story their editors wanted, in light of Roy Gutmanfs story about the Omarska "concentration camp." At this refugee camp, this British news team chose a tall, emaciated man standing behind a barbed wire fence. This man's appearance resulted from having had tuberculosis as a child, and the barbed wire had been there since before the war. However, this photo was published in influential newspapers such as the New York Times, The Times of London, the Daily Mirror and was accompanied by the phrase "concentration camp."[4]

c. Upsurge in

International Awareness – Voices

Justifying Intervention

The influence of this photograph on the general public was huge, and it raised a strong antipathy toward the Serbs, the people who allegedly created concentration camps for Muslims. Concentration camps had also been set up by Bosnians and Croatians, but the international media were not excited to report it, since Milosevicfs was already gSaddamized,h and it was hard to report on Serbiafs side. Furthermore, almost all foreign journalists stayed in Sarajevo, the most cosmopolitan city in former Yugoslavia, which was pro-Muslim. This kind of media control was everywhere, and it was extremely difficult to maintain a neutral position both inside of Yugoslavia and outside of Yugoslavia.

In the Bosnian war, Serbian forces had two objectives: to expand and link up the territories they controlled, and to eliminate the non-Serb population in these areas. By the summer of 1992, the Serbs controlled about 70 percent of Bosnia. They laid siege to Sarajevo, Bosniafs capital, with artillery and snipers. Because of this situation, in 1992, the UN Security Council deployed 7,000 UNPROFOR troops in Bosnia.

In May 1993, the Croats launched a war against their former Muslim allies for control of central Bosnia and the Muslim portion of Mostar, the capital of the Herzegovina region. The Muslims also held their own against the Croats in central Bosnia. Croats and occasionally also Muslims carried out massacres.[5]

The Vance-Owen peace plan made at an international conference was widely considered the most promising proposal. It was put forth in 1992 and 1993. It was at one point accepted by all parties except Bosnian Serbs. Their refusal led Milosevic, who feared that international pressure might grow into foreign military intervention, to temper his relation to Karadzicć and reduce Serbiafs support of the Bosnian Serb army.[6]

d. The Changing Function

of the UN and NATO

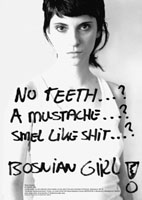

Sejla Kameric Bosnian Girl 2003

Go to Another Expo – Beyond the Nation-State

In the spring of 1993, the UN established six gsafe areash for the Muslims; these were towns where UNPROFOR troops would protect them from attack. These areas were Sarajevo, and the Muslim towns of Bihac, Tuzla, Gorazžde, Srebrenica, and Zepa. In May 1995, renewed Serb bombardment of Sarajevo triggered NATO air strikes on Serb forces. The Serbs responded by holding more than 350 UNPROFOR soldiers hostage, and they were released only after protracted negotiations. In July, Serb forces overran Srebrenica and Zepa. In Srebrenica they massacred thousands of Muslim men and boys, captured in the presence of a small Dutch UNPROFOR contingent. The United States and NATO reacted to these events with more force to end the conflict.[7]

In August, NATO aircraft launched their first serious attacks on Serb positions in response to a murderous mortar attack on a crowded market in Sarajevo. The identity of those responsible for the attack is still not clear. Finally, in November 1995, Tudjman, Izetbegovic, and Milosevic signed the Dayton Peace Accord, after three weeks of intensive negotiations and pressure from the United States.

French NATO Soldier in Sarajevo in January, 2004 (Photo by Shinya Watanabe)

The Dayton Peace Accord dictated a constitution that established a formally united Bosnia made up of two entities; the Muslim-Croat federation, which, although it takes up 51% of Bosniafs territory, exists almost only on paper, and the Serb Republic, which takes up the remaining 49 percent. Bosnia became, in effect, a protectorate of NATO, the European Union, and the UN. It has remained so until today.

e. Kosovo War

Uros Predic: The Kosovo Maiden 1917

Kosovo is sacred to the Serbs, since it is the cradle of their culture, church, and statehood. In 1389, in the Battle of Kosovo, the Serbs were defeated by forces of the Ottoman Empire, an event that has become the most important event in their history. However, by the nineteenth century the population of Kosovo was predominantly Albanian, and in the late twentieth century Albanians accounted for more than 80 percent of its population. Many Kosovar Albanians aspired to have their own nation-state or to unite with neighboring Albania.

Kosovofs Albanian majority periodically rebelled against Serbian and Yugoslav authority ever since Serbia first annexed Kosovo as a result of the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. Yugoslaviafs Communist leader Tito granted authentic and broad autonomy to Kosovo after 1968, permitting a large measure of self-rule by Kosovofs ethnic Albanian Communist elite.[8]

In 1981, the Yugoslav government brutally suppressed mass demonstrations by Kosovar Albanians, who were demanding that Kosovo be granted the status of a republic within Yugoslavia. Many of Kosovofs decreasing Slav minority responded to the turmoil by leaving Kosovo. That minority declined from 20 percent to 10 percent of the population in the 1980s. Under these circumstances, most Serbs earnestly applauded Milosevicfs abolition of Kosovofs autonomy in 1989 and 1990 and his accelerated repression of the Kosovar Albanians.

During the time of turmoil, an underground Kosovar Albanian government, headed by Ibrahim Rugova, was elected in 1992. Rugova declared Kosovofs independence, and continued to create an underground state with its own schools, elections, government, and taxes. Rugova insisted that passive resistance and civil disobedience were the only appropriate weapons to use against Serbian rule and repression. For several years, his approach seemed to be universally accepted by Kosovofs Albanians, and people started to call Rugova gKosovofs Gandhih because of his pacifist approach. Deeply involved at the time in the wars in Croatia and then Bosnia, Milosevicfs regime tolerated Rugova and his underground state.

f. Emergence of the Kosovo

Liberation Army

However, Rugovafs strategy of passive resistance failed to win any significant concessions from the Serbian government. By the late 1990s, the failure of Rugovafs strategy had eroded his popularity and authority. In late 1997 and early 1998, armed Kosovar Albanians calling themselves the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) emerged to launch repeated attacks on isolated Serbian police stations.

In March 1998, Yugoslav army units joined Serbian special police in a major effort to wipe out the KLA and its supporters. Hundreds were killed, and more than 200,000 people, mostly Kosovar Albanians, were driven away from their homes. Many of these people and their relatives joined the KLA, which grew from an isolated tiny band into a formidable guerrilla force of several thousand. In July 1998, the KLA briefly controlled an estimated one-third of rural Kosovo before being driven back into the hills by a Yugoslav counteroffensive that claimed more and more civilian victims.[9]

In October 1998,

intense diplomatic pressure and the threat of NATO air strikes forced Milosevic

to agree to withdraw some troops and police and to take part in negotiations

with Kosovar Albanian leaders that were aimed at restoring some degree of

autonomy to Kosovo. However, the

KLA regrouped to continue its attacks, and Milosevic ceased to honor the

agreement. Serbian forces began a

major offensive against Albanian villages in early 1999. NATO leaders interpreted this offensive

as the beginning of systematic ethnic cleansing of Kosovofs approximately 1.5

million Albanians. Under renewed

international pressure, Milosevicfs government and Kosovar Albanian

representatives (including KLA leaders) participated in internationally

sponsored negotiations in Rambouillet, France, in February and March 1999. Milosevic rejected a peace plan that

called for placing NATO security forces in Kosovo with unhindered access to all

of Serbia Montenegro (FRY).[10](For

more detail, refer III f. Rambouillet Peace Treaty – Corruption of European

Politics)

g. The Bombing of Serbian

Military and Cities by NATO

In late March, NATO forces led by the United States began air strikes, using both piloted aircraft and cruise missiles to attack military and other targets throughout Serbia- Montenegro. Serbian assaults on ethnic Albanians by police and paramilitary units intensified, and the Yugoslav army destroyed villages and forced residents to flee. Most NATO leaders rejected the idea of a ground invasion of Serbia-Montenegro, so NATO intensified its air strikes in April and May. The targets of the attacks now encompassed bridges, railroads, oil and electricity facilities, and factories throughout Serbia-Montenegro, including those in downtown Belgrade and other cities.

The UN estimated that nearly 640,000 people were forced out of Kosovo, fleeing NATO bombing as well as Serbian assaults, from late March to the end of April 1999. Most of them fled to Albania or the FYROM (Montenegro), causing enormous damage and stress in those fragile states and their economies. In May 1999, the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia) indicted Milosevic and four other senior Yugoslav officials for war crimes in Kosovo. Later, the ICTY examined and rejected the demands, and it also rejected indicting the leaders of NATO for war crimes.

On June 3, 1999, Milosevic finally agreed to a peace plan that reaffirmed formal Serbia-Montenegrofs sovereignty over Kosovo as NATO and UN protectorate. A diplomatic envoy from Russia, as a historical friend of Serbia, played a major role in the negotiations between Serbia-Montenegro and NATO that led to the agreement. NATO suspended its bombing after Serbian forces began withdrawing from Kosovo on June 10. The UN Security Council authorized the occupation of Kosovo by an international peacekeeping force called KFOR (Kosovo Force). Most of KFORfs 50,000 troops were from NATO members, but KFOR also included units from Russia and other countries that were not members of NATO.[11]

h. Media Report on Kosovo – Who are the People in

Kosovo? – Strategy of the United States and the European countries

Surprisingly, European and American media had not reported well the religious background of Albanians, who are Muslims, and other minority groups in Kosovo. If more westerners were aware of the background of Kosovar, some might wonder why the European Union and the United States supported Muslim people, because Muslims were supposed to be on the side of terrorists in their view.[12] Because of the media bias, Albanian people were reported merely as victims of Serbian fascism. Furthermore, the year 1999 was the fiftieth anniversary of NATO, and to bomb Yugoslavia was the best way to demonstrate the influence of NATO and the new meaning of NATO.

Kosovo had been part of the New Yugoslavia Federation (Serbia- Montenegro), and most Kosovars desired to be independent from the New Yugoslavia Federation, especially after Milosevicfs abolition of Kosovofs autonomy in 1989 and 1990. However, almost all European nations were against the recognition of Kosovofs independence or unification with Albania. If European nations recognized the independence of Kosovo, they would have to recognize all demands of independences by minorities in Europe, such as those in Basque regions in Spain. If European nations admitted the unification of Kosovo with Albania, this would show European support of the idea of Greater Albania, which contradicts the rationale for NATOfs intervention to oppose Serbiafs attempt to create Greater Serbia.

If NATO intruded because of Serbian human rights violations in Kosovo, this would violate the old world order, since the old world order prohibits intervention in the civil wars of other nations. However, if they apply the terms of the new world order that was developed by the United States, human rights violations in Kosovo would be grounds for NATO to intrude to put a stop to such abuses.

In Europe, most countries were unwilling to expand their budgets for defense, and also did not want to be followers of the United States. However, if the United States would accuse European countries of allowing human rights violations, European countries could not protest such accusations. As a result, the aerial bombing by NATO, led by the United States, began. However, because of this aerial bombing, the condition of Kosovo became worse. The oppression by the Serbian Army became intense, and 60,000 people became refugees in five days. Furthermore, the aerial bombing of NATO was not sanctioned by a UN resolution, which violated the North Atlantic Treaty. The North Atlantic Treaty declares that NATO can use force only when a NATO member state was attacked, or the UN required sending military forces. If the United States tried to get the agreement of the UN, Russia and China would have used their vetoes for this decision. That is why the United States ignored the UN in this case.

However, after NATOfs bombardment of Serbia, antipathy towards western European countries and the United States increased, as did support for Milosevic. The bombing that started in March 2000 was stopped when Milosevic decided to withdraw from Kosovo. Then the UN force was stationed in Kosovo, but the problem of Kosovo was not solved and came to a deadlock.[13] In addition, the party of Milosevic and Vojislav Seselj, ultranationalists and, both of them under indictment for war crimes in The Hague, won the largest number of seats in parliamentary elections on December 29, 2003.[14]

Furthermore, the bombing of Yugoslavia became more important as a historical event, revealing the emergence of the unilateralism of the United States.

Go Next: III. Interpretation and Censorship